The first few months that I stayed in China I started to learn the language in the small town of Hai’an, Jiangsu. I was not learning the national language but the local dialect. A colleague pointed it out when instead of saying “Ni hao” I said, “Ni hoa.” More words in the regional dialect inverted the “a” and the “o.” Later I met more locals that did not speak the national language, but only the local dialect. One middle-aged lady told me, “I am sorry but I do not understand Chinese.” I understood most of what she said since the dialect Hai’anhua sounded enough like standard Chinese. She is one of the 400 million Chinese who can’t speak standard Chinese. I lived in a small agricultural town and knew that the farmers hardly left their plots of land, let alone Hai’an. As one goes farther away from the town, similar dialects like Hai’anhua are bottled-up in their own island-like areas.

I am reminded of one of my favorite history books named Southern California: An Island on the Land by Carrie McWilliams. The book mentions the state of California in the U.S.A. and how it is a unique place from the rest of the country. Most people can name a place or two in their countries that are so unique that they are not like the rest of the nation. Chinese author Lin Yutang in his 1935 classic My Country and My People comments that China is so big and varied in languages and cultures that he can’t write about them all in one book, let alone one chapter. To be succinct he divides China between north and south. But others can divide China into six or seven regions like the northwest, southwest etc. I will take it one step further by saying China is best thought of as an arquipelago. Within these areas exist islands on the land where some folks, especially the older people, do not like to leave. One area may have much in common with surrounding areas, but they are still different. I will just focus on the uniqueness of my present town Jintan, Jiangsu exemplified by the two local languages.

In Jintan two major dialects are spoken: One is Jiang Bei Hua (also called Su Bei Hua), literally north of Jiangsu Language, and the other is called Wu Yu (Wu Dialect), also called Ben Di Hua, literally “local language”. Over sixty-years ago the demarcation line between these two languages used to be Nanjing and the Yangtze River. Jintan became the new border line of Wu and Jiang Bei Hua because of World War II. When Japanese forces were besieging Nanjing, people from there and surrounding cities migrated to Jintan. The south of Jiangsu stretching from Changzhou, Liyang, Wuxi, Suzhou, to Shanghai speak the Wu Dialect. Differences exist between the cities, but the people can still communicate with each other in Wu. The cities north of the river like Taizhou, Yangzhou, and Hai'an up to Anhui speak Jiang Bei Hua.

According to Jintan locals about 60% of the population use Jiang Bei Hua and 40% use Wu Yu as their primary language. Most locals are knowledgeable in both languages to differing degrees.

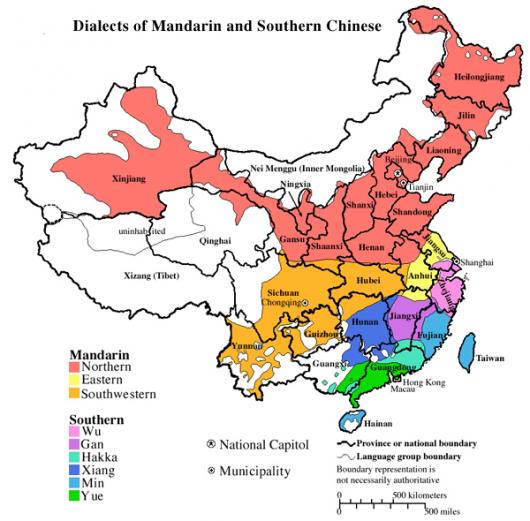

For linguists Jiang Bei Hua is a Mandarin language that originated in northern China. It has similar sounds and grammar to the Standard Mandarin but is still unique enough to be under the classification of Eastern Mandarin. Mandarin, from where standard Chinese comes from, is divided into Northern, Eastern, and Southern.

Wu is one of the oldest dialects in China. Its rose during the Spring and Autumn Period (771 B.C.-403 B.C.) and spread further during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.). At first the standard form of the language was considered to be Suzhou. With the later rise of Shanghai, the Wu Dialect was more identified with Shanghai.

Photo: Chinesetranslationpro.com

Chinese people usually name their local language after their town. They just add the word “hua” at the end to signal their own variant. Logically as one gets farther away from a town the less intelligible the local variations of the language become. For example, by the time one travels from Jintan to Nantong the original people there speak a dialect of Wu called Qihai Dialect. Others in the same city speak Jianghuaiguanhua, commonly known as Nantonghua, a language completely different than the first two mentioned. Some Jintan people comment that Qihai it is not Wu Dialect at all. I suspect people form Nantong would say the same about Jintan.

Family obligations, familiarity, the veneration of ancestors, and being comfortable in their own language are some reasons why Chinese people do not venture outside their hometowns for long. My colleague at work Mr. Lu has his parents from An’lu, Hubei living at his home to take care of his newborn. But when the mother-in-law comes, who can speak Chinese, he has to do the translating: “My parents never traveled much outside of my hometown. They think they are in Japan. I tell them to write in characters to my mother-in-law [to communicate].” To Lu’s parents spoken Chinese remains as much a mystery to them as the English he teaches. The Chinese are more comfortable in their own islands per say.

Standard Chinese was not developed until 1955, and initially there were not enough teachers to spread it. Because of a lack of proper instruction, older folks including undereducated Chinese are not all fluent in standard Chinese. When these people went to school there was no model or they were not in school long enough.

My own Chinese tutor, Miss Wen, told me that her grandmother living on the real island of Zhoushanqundao near Shanghai only leaves twice a year. Her dialect of Zhoushanhua is based on the Wu Dialect spoken in Ningbo, but is mutually understandable with the Shanghai Dialect. Wen’s grandmother has had a curious education in Chinese languages: “My grandmother has learned some standard Chinese from watching television and she even knows some English words. She can understand the dialect of Shanghai but is not so conversant in it.” Once the grandmother’s business is done it is back to the safety of her island on the sea.

Local teacher Liu Xia would like to see her parents travel more ouside on Jintan. She comments, “My parents can understand Chinese but they are not fluent in it. They do leave for visits and vacations, but not for too long.”

Lin Yutang wrote that Chinese people do not produce children but grandchildren. In Jintan many children are being raised by their grandparents who have good knowledge of one or both languages, even though their standard Chinese maybe lacking. Thus Jintan will continue to be a tri-lingual place, and other places in China bi-lingual at least for a few more years.

Tags:Language & Culture

All comments are subject to moderation by eChinacities.com staff. Because we wish to encourage healthy and productive dialogue we ask that all comments remain polite, free of profanity or name calling, and relevant to the original post and subsequent discussion. Comments will not be deleted because of the viewpoints they express, only if the mode of expression itself is inappropriate. Please use the Classifieds to advertise your business and unrelated posts made merely to advertise a company or service will be deleted.

Please login to add a comment. Click here to login immediately.

i agree with the reasons why Chinese do not venture outside their hometowns for long,especially that we are enjoying the comfortable in their own language. maybe that is one reason that i am not eager to go abroad. haha! but when i am in an English speaking country, i have a strong ambition to learn the language well. the surroundings are affecting our sense to language.

Jun 16, 2014 19:40 Report Abuse

A well-written essay about one of the few things China finds both pride and trouble in. I am a translator so this topic instantly caught my attention. Some historical facts are interesting, and the story of Miss Wen reminded me of my visits to Guiyang, a southern city that speaks a dialect originating from Xi Nan Guan Hua, literally southeastern official language. Imagine how strange it is when some Chinese despise you just because you do not speak in their dialect you often have trouble understanding! I am sure glad that Putonghua came along to bind China together, but it's a sad thing to have so many dialects and languages disappearing so fast and making the world a duller place. Guess diversity can also be a double-edged sword....

Jun 02, 2014 20:15 Report Abuse